Bronte Metekingi – STUFF

Seasoned firefighter John Rowe attended a recent callout where he had to perform CPR on a 3-month-old baby. The child didn’t make it.

Rowe later found out the death was being treated as a suspected murder. He thought of his own grandchild.

He called the 0800 mental health support number provided to firefighters – they were “too busy”.

For Rowe, this was the final straw. After 32 years, he no longer works as a frontline firefighter.

On Monday, members of the Professional Firefighters Union went on a partial strike, refusing to complete any mandatory administrative tasks, like gathering statistics, non-essential paperwork, training and attending conferences.

The union and Fire and Emergency New Zealand (Fenz) have hit an impasse after more than a year of bargaining, with the union not ruling out escalating strike action if a deal cannot be reached.

There are issues with pay, staffing levels and equipment, but top of firefighters’ list of grievances is a lack of mental health support and awareness.

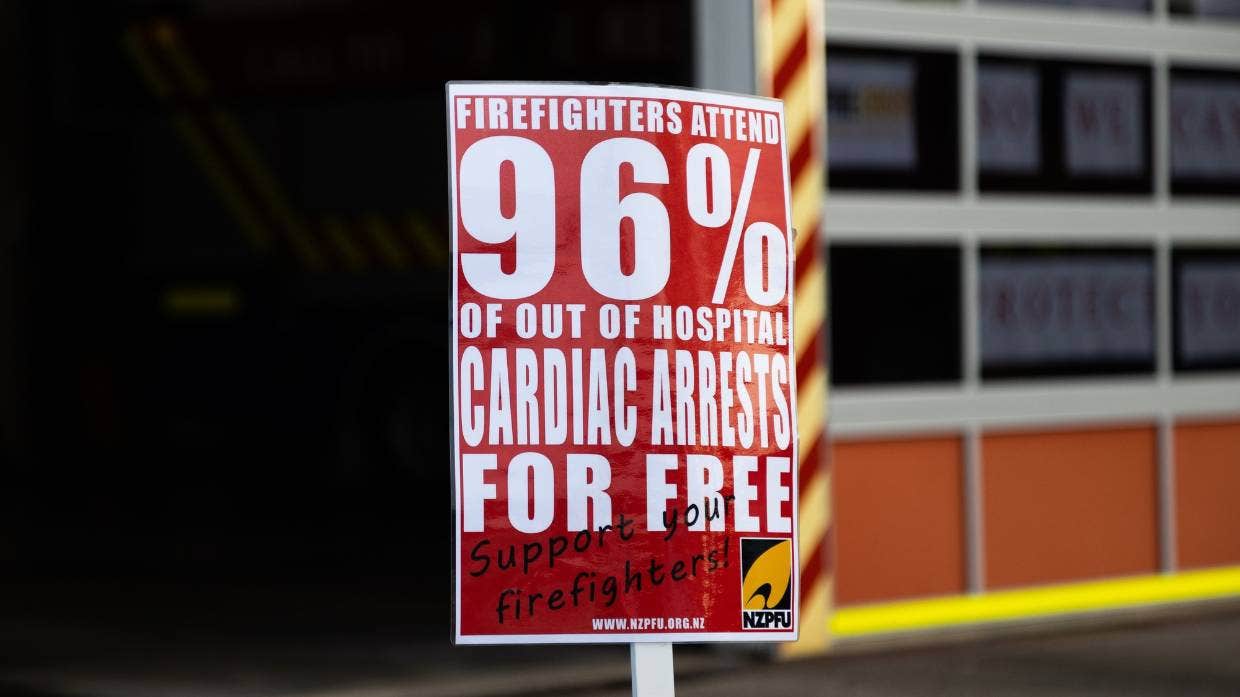

Porirua firefighter Jay Elkington said fire crews were almost always the first on the scene when called to a “purple incident” – that’s when a person is near-death or dying.

JERICHO ROCK-ARCHER John Rowe no longer works as a frontline firefighter after reaching the “final straw” on the job.

Since 2013, firefighters have been required to respond to these incidents alongside ambulance staff, but they felt ill-equipped to deal with what they faced.

“We’ve got a bag of bandages, Gladwrap, plasters and bottles of salty water on hand to respond to serious car accidents, suicides and stabbing victims.”

In the past week, Elkington has attended three incidents where someone required CPR. In two of these cases, the person did not survive.

“Being in the job so long, you become desensitised to a certain degree,” he said. But it was the families that stuck with him.

“You’ve got a crying wife …. pleading with us to bring them back. Or the children. We don’t get trained, or any help, to deal with that stuff.”

When Elkington drives past houses in his neighbourhood, he remembers what happened there – the incident, the wife, the children. But he doesn’t know what happened after they closed the ambulance door.

“It would be nice to know if they make it or not. It would give us some closure.”

Elkington said he wanted officers to be trained to recognise what trauma looked like and for processes that removed the pressure on firefighters to self-report.

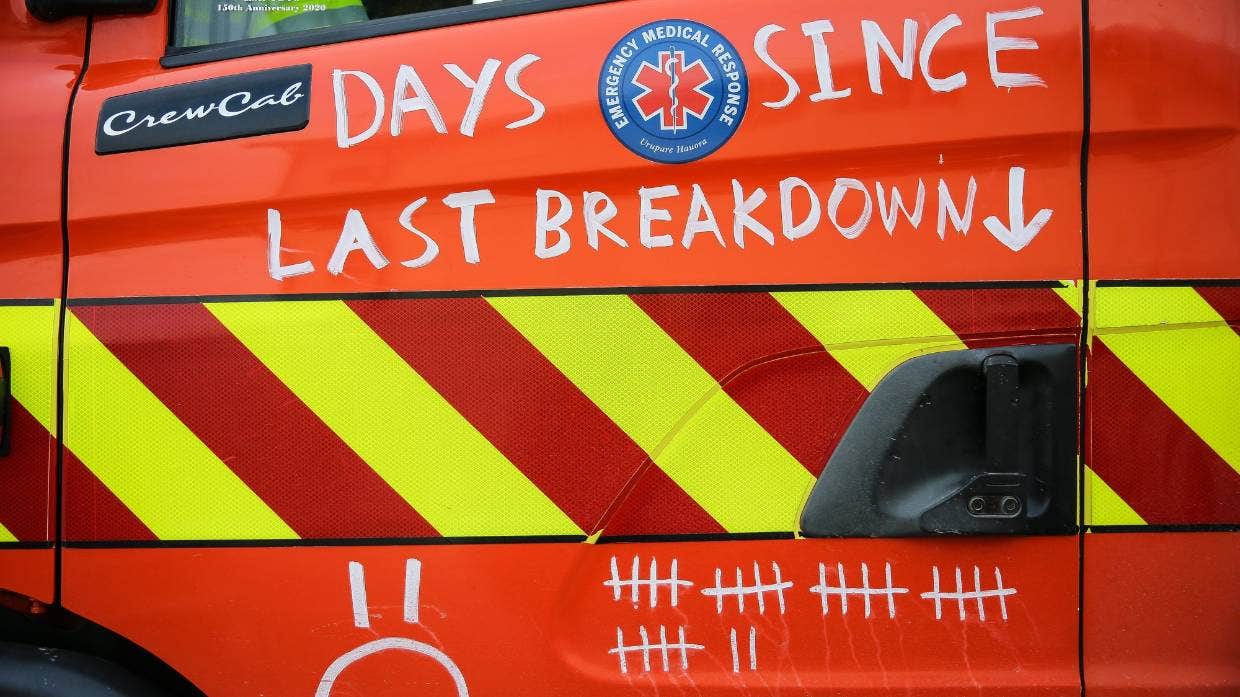

JERICHO ROCK-ARCHER Porirua firefighters display information about their working conditions and lack of mental health support.

“I don’t know what mental health trauma looks like, or if I am suffering from it.”

Colleague Bret Burrows said, from the coal face, the current support systems and processes felt like “a tick box exercise”.

“This system relies on self-referral and if someone is struggling, they aren’t always in the right frame of mind to self-refer,” he said.

“A system where professionals routinely monitor firefighters’ wellbeing is needed.”

Officially, crews are supposed to do a debrief after every callout, but whether that happened depended on the severity of the incident.

The effect was cumulative, he said. “While you’re still processing one, you get pinged, and you have to go to another one. It all adds up over time.”

The firefighters didn’t feel supported by management.

JERICHO ROCK-ARCHER Alan Collett, union local secretary in Wellington, says in some instances firefighters have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress injury (PTSI).

Fenz deputy national commander Brendan Nally said firefighters were provided a range of free counselling and professional psychological support services. Counselling was also available to firefighters’ immediate family.

The national body had offered to work with the union to improve and develop mental health support and education, he said.

But it isn’t just the nature of the incidents, it’s also the number of hours firefighters are having to work.

All the firefighters who spoke to Stuff said they’d had to work between 86 and 100 hours a week on countless occasions, in an effort to keep fire trucks on the run and prevent Wellington fire stations closing for the day.

Some firefighters in the region were racking up more than 300 hours a month due to staff shortages. These shortages also made responding to incidents more dangerous.

Nally said firefighters worked 42 hours a week on average, before overtime, based on two-day shifts, followed by two night shifts, and four days off.

AIMAN AMERUL MUNER/STUFF Officially, crews are supposed to do a debrief after every callout, but whether that happened depends on the severity of the incident.

“I am aware some personnel occasionally work long hours, and like many organisations, we have recently been impacted by absences due to Covid-19.”

Nally said he appreciated the “extra mahi” and the need to balance that against fatigue and other pressures, while pointing to the organisation’s fatigue management policy.

In a previous statement, Fenz chief executive Kerry Gregory said personnel occasionally worked long hours, but he was not aware of anyone routinely doing 80, 90 or 100 hours a week.

Burrows said it was hard to hear FENZ downplaying their struggles.

The recurring response was “we’re looking into it”. But that wasn’t good enough, he said.

“It’s like, we’re just going to throw some more money at it and a bunch of people are going to sit around and talk about it, but it won’t actually affect what’s happening.”

Burrows said the extra hours and stress had a knock-on effect. “If you’re selling your free time, something’s got to give – whether it’s family life, your loved ones, your own mental health and wellbeing.”

Wattie Watson, secretary of the New Zealand Professional Firefighters’ Union, said all these issues had compounded to cause a fire crisis.

The parties were deadlocked at the end of one day of mediation on Thursday and Fenz had declined to meet for any further meetings until the union put forward a lower remuneration claim, she said.

“The relationship is at its lowest ever.”

Where to get help:

- 1737, Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 to talk to a trained counsellor.

- Anxiety New Zealand 0800 ANXIETY (0800 269 4389)

- Depression.org.nz 0800 111 757 or text 4202

- Kidsline 0800 54 37 54 for people up to 18 years old. Open 24/7.

- Lifeline 0800 543 354

- Mental Health Foundation 09 623 4812, click here to access its free resource and information service.

- Rural Support Trust 0800 787 254

- Samaritans 0800 726 666

- Suicide Crisis Helpline 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO)

- Yellow Brick Road 0800 732 825

- thelowdown.co.nz Web chat, email chat or free text 5626

- What’s Up 0800 942 8787 (for 5 to 18-year-olds). Phone counselling available Monday-Friday, noon-11pm and weekends, 3pm-11pm. Online chat is available 3pm-10pm daily.

- Youthline 0800 376 633, free text 234, email talk@youthline.co.nz, or find online chat and other support options here.

- If it is an emergency, click here to find the number for your local crisis assessment team.

- In a life-threatening situation, call 111.

CHECK ITS ALRIGHT

CHECK ITS ALRIGHT